Metal Recovery from Electric Vehicles

By Paul Fears | 06 April 2020

Click here to see our solutions for metal recovery from Electric Vehicles

Mining the Urban Environment

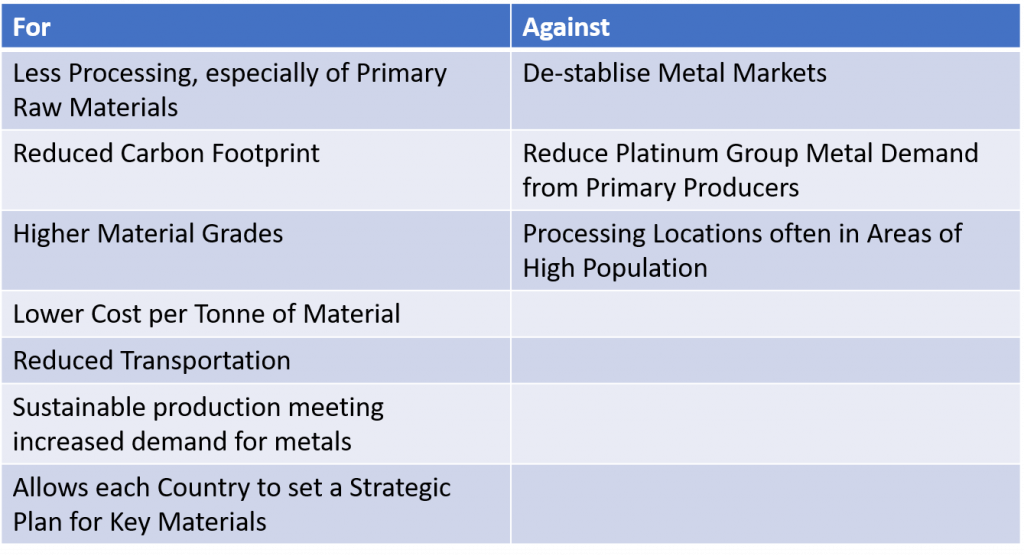

The anticipated global increase in production and consumption of electronic goods and electric vehicles puts a huge strain on raw material reserves. Subsequently, the focus has turned from mining raw materials to reclaiming, reusing and recycling secondary materials. This is known as ‘Mining the Urban Environment’.

The strategic nature of critical metals has resulted in some governments partially controlling at least some of the supply chains of these secondary materials.

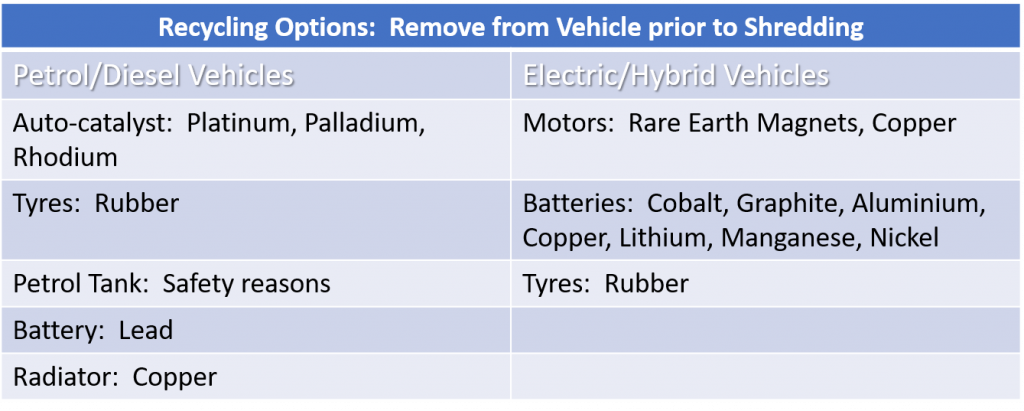

Many electronic and high-tech products or high-important waste streams already have established recycling routes such as:

- Recycling of Platinum Group Metals from Auto-catalyst (well established technology);

- Recovery of Platinum Group Metals from road dust (one commercial site in UK;

- Recycling of specific items from petrol and diesel cars, i.e. battery (Lead);

- Auto-catalyst (Pt, Pd, Rh), radiator (Cu) plus general base metal recycling;

- Processing of Electronic Waste (WEEE) (Cu, Al, Ag, Au, Platinum Group Metals);

- Domestic battery recycling (Lithium) + others metals;

- Plastic and glass recycling (mature technology);

Technological developments continue to change the recycling landscape, altering the location and amount of valuable metals in a waste product and, often, increasing the complexity of recovery. Such changes present huge ever-changing challenges to the recycling sector. Valuable sources of metals in the future include:

- Platinum Group Metals from medical waste;

- Rare Earth Elements from auto-waste, computer hard-drives, mobile phones and wind turbines;

- Graphite from steel waste (Kish graphite);

- Lithium, Cobalt, Graphite, and Nickel from Li-Ion Car batteries;

- Germanium/Gallium from coal fly ash;

Successful ‘Urban Mining’ recovers metals and other materials from such waste and reduces the demand on primary raw material reserves. Additionally, recycling broadens the source location of the materials, often becoming more localised. This reduces transportation costs and stabilises prices, especially of geographically-limited materials such as Neodymium Magnets, of which over 90% are supplied from China.

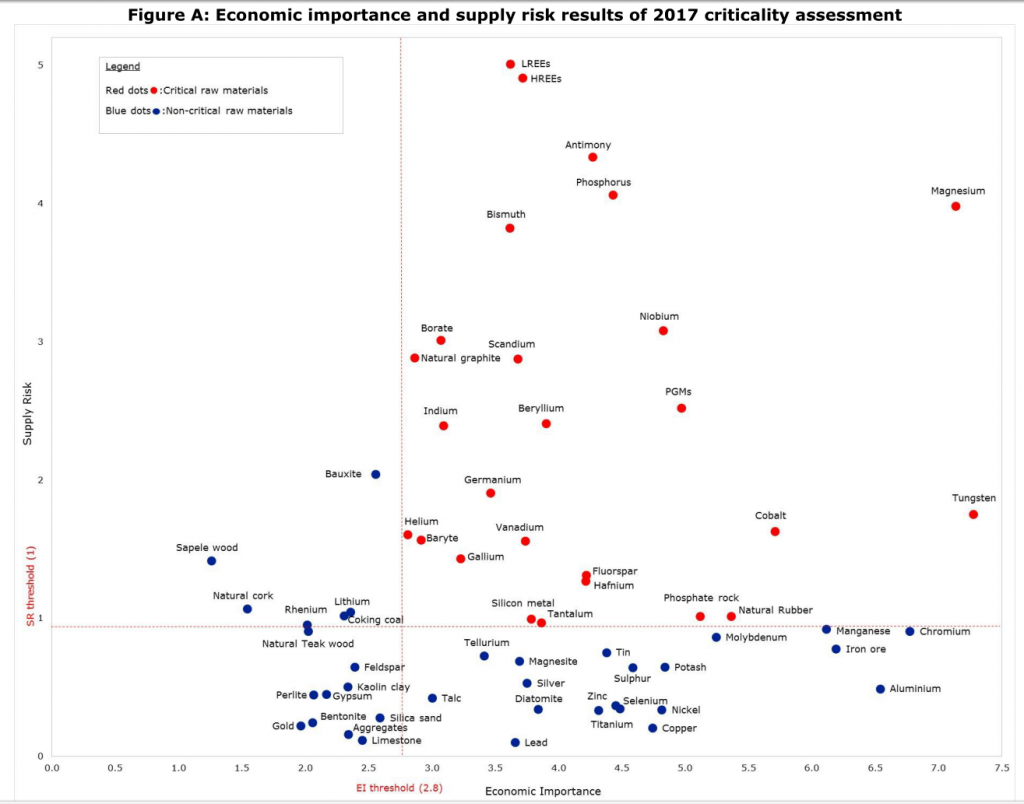

Definition of Critical and Strategic Materials

Whilst considering ‘Urban Mining’, the European Union has produced a critical assessment based on supply issues and economic importance for key materials, which is updated on a regular basis.

The European Union identified Rare Earth elements as highly critical. Rare Earth elements are key to the manufacture of electronic goods, wind turbines, computer hard-drives, and electric and hybrid vehicles (which use a far greater quantity of rare earth magnets than traditional combustion engines). To address the anticipated supply issue of Rare Earth elements, the EU is funding research recycling projects such as SUSMAGPRO and DEMETER (of which Bunting is a key member and contributor along with the Magnetic Materials Group (MMG) at the University of Birmingham). The primary objective is to identify processes to recover, reuse and/or recycle Rare Earth Magnets from secondary sources and develop technology to create a new generation of ‘recycled’ magnets with the same magnetic performance as magnets made from primary materials.

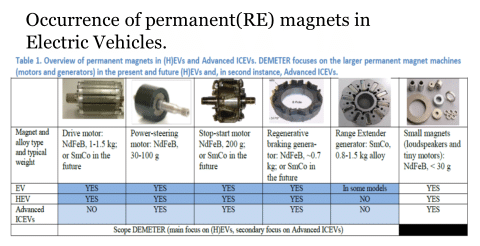

Rare Earth Magnets in Electric Vehicles

Rare Earth Magnets (Neodymium and Samarium Cobalt) feature in many key electric vehicle components including motors (drive motors, power-steering, stop-stop motor, wind-screen wipers, electric windows, etc), generators (regenerative braking, range extender), speakers and many small motors. Each new electric car is estimated to contain between 2 and 5 kg of Rare Earth magnets.

Critical Materials

Platinum Group Metals (PGMs – Platinum, Palladium, Rhodium) are also listed on the EU list of critical and strategic materials. These feature as key components in capacitors and sophisticated electronic components. Recycling companies are particularly interested due to the high market price of the PGMs, especially as they are becoming more common in electronic waste streams and auto-shredder residues.

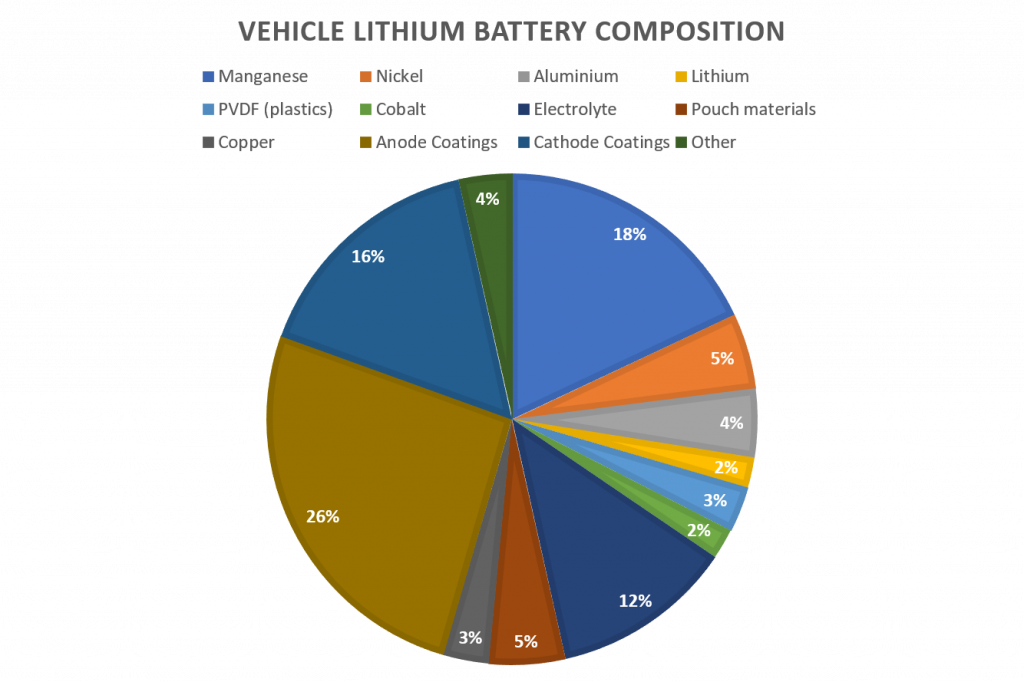

The use of Lithium-ion batteries, with their recharging capabilities, continues to rapidly increase. These are found in electronics goods such as laptop computers, mobile phones, cameras, power tools and many other everyday items. The demand for such batteries is anticipated to further rise sharply with the growth in Electric Vehicles, along with Rare Earth Magnets used in drive motors. Such increased demand could create supply issues for ethically-sourced raw materials such as Cobalt, Graphite, Nickel and Lithium.

The future occurrence of electric and hybrid vehicles at auto scrap processing plants will create a fresh set of challenges to the recycler. The change in the nature of materials, with an increase in valuable secondary materials, makes the recycling of high value components more economically viable.

Re-Use versus Recycle

When the operating efficiency of Li-ion automotive batteries drops below a specified level, replacement is the only option. The fate of the removed batteries depends on the condition and any dead cells. The favoured option is for the battery to be re-used in less a demanding application and a number of companies now offer this service. Companies such as Aceleron are now re-purposing functioning batteries for less demanding power storage on a global scale. However, once the useful life of the battery ends, there is a need for safe disposal or recycling, with recycling being the preferred option.

The commercial and ethical drivers for the re-use and recycling of batteries include:

- Lower CO2 Cost;

- Access to and control of Strategic Elements & Critical Materials;

- Ethics of mining raw materials including the environmental cost and welfare of people (workers and local communities);

- Potential difficulties in exporting battery waste. Countries such as China continue to impose stricter restrictions and BREXIT may cause difficulties with exports to the EU;

- Sustainable use of Earth’s resources (Cobalt, Graphite, Lithium);

Structure and Chemistry of Lithium Ion Vehicle Batteries

The chemistry and design of electric vehicle batteries continue to evolve with improved operating efficiencies.

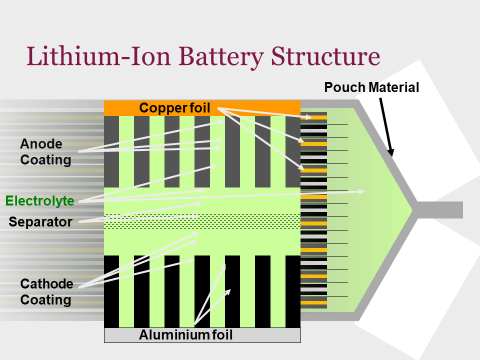

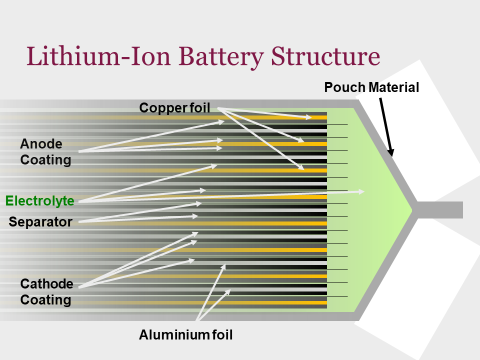

Conventional Li-ion battery designs consist of:

- Copper foils coated in Graphite to form the anodes;

- Aluminium foil coated in oxides of Cobalt, Nickel, and Manganese to form the cathode (Table 3);

- The electrolyte comprises Lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) dissolved in a mixture of organic carbonates – mostly ethylene carbonate, diethyl carbonate, and ethyl-methyl carbonate with trace additives for electrolyte performance.

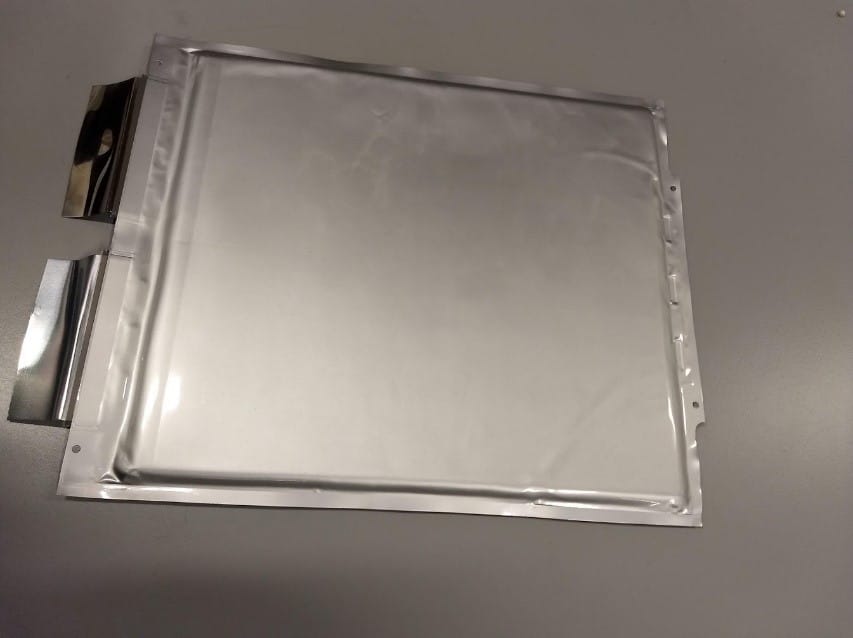

The battery pouch from a Li-ion Car Battery will vary in design and chemistry based on the specification of the individual vehicle manufacturer.

In the recycling process, the first step is to safely discharge the battery pouch. The battery pouch is then shredded and dried, leaving a mixture of plastics, anode material, cathode material, and black powder (black mass). The process is very similar to that seen in an operation recycling electronics waste (WEEE).

Once shredding has liberated the individual materials, the application of physical separation techniques enables segregation into concentrations of plastic, anode, cathode and black mass. The particle size distribution of the shredded battery is determined by the shredder blade geometry and screening. The physical separation technology includes Magnetic Separators, Eddy Current Separators and ElectroStatic Separators.

Research Funding for Li-ion Vehicle Battery Recycling in the UK

In January 2018, the Faraday Institution announced ReLiB, a major research project in Li-ion car battery dismantling, reuse and recycling (ReLiB). The project was awarded to a consortium of Universities headed by the University of Birmingham.

The aim of ReLIB is to facilitate a circular economy in lithium ion vehicle batteries, tackling the most demanding technical challenges in sensing, gateway testing, sorting, re-use and recycling. Specialists in Life Cycle and Techno-economic assessments review the developed processes. New business models and regulatory frameworks are also developed in conjunction with the value chain to promote the collection of vehicle batteries from a range of sources.

Successfully physically processing the waste batteries is fundamental to the project. The right combination of shredding, physical segregation and sorting (Magnetic Separation, Eddy Current Separation, ElectroStatic Separation and Froth Flotation) will separate and concentrate metallic and metal oxide materials from the battery structure. Plastic components are sorted via density separation and additional electrostatic separation.

Why the Physical Separation Route to Recycling?

Recycling batteries using physical separation techniques offers a number of important benefits.

- There is no change in the chemistry or structure of material;

- Separation based on different physical properties of the material;

- Low energy usage;

- Adapting existing and proven technology;

- Low operating costs;

- Enables the concentration of individual materials for expensive downstream processes, reducing overall processing costs;

Typical Separation Equipment

Ferrous and Non-Ferrous Metal Separation

The project team acquired a pilot plant scale Metal Separation Module (incorporating an Eddy Current Separator and high strength Rare Earth Drum Magnet) for the ReLiB project from Bunting. The Metal Separation Module separates plastic pouch material and polymer battery structures from the anode and cathode materials.

In operation, shredded material is evenly fed via a vibratory feeder onto the rotating surface of a Drum Magnet. Weakly and strongly magnetic materials are attracted, held and deposited away from the remaining non-magnetic material.

The second stage focuses on the separation of non-ferrous metals using the Eddy Current Separator.

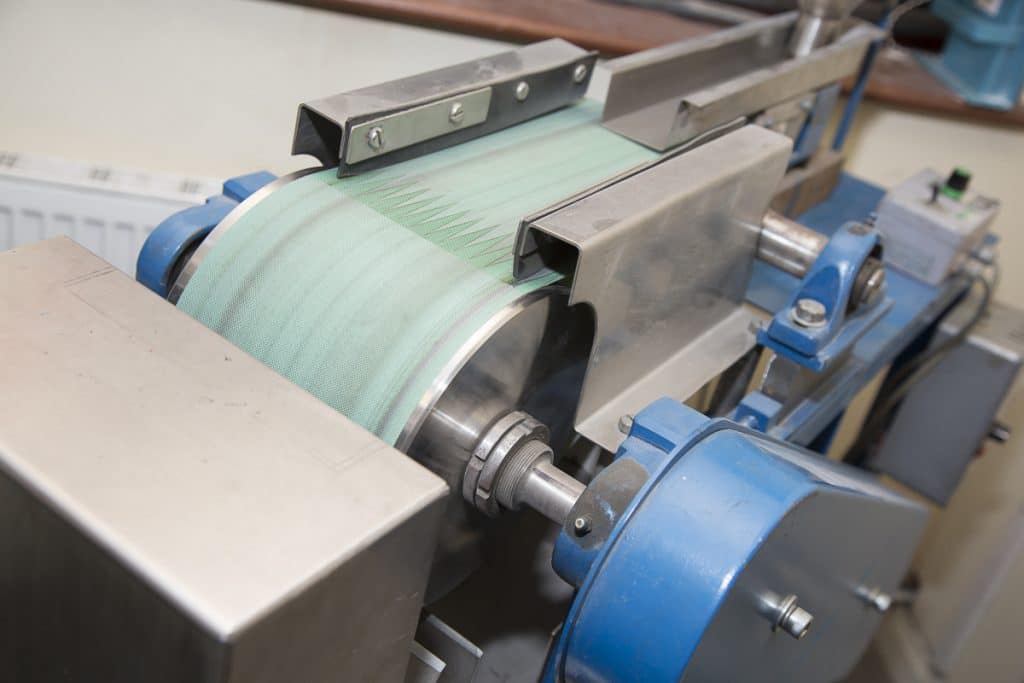

An Eddy Current Separator consists of a short belt conveyor with a drive located at the return end and a high-speed magnetic rotor system installed at the discharge end. The magnetic rotor, which is positioned within a separately rotating non-metallic drum, revolves at around 3000 revolutions per minute during operation, whilst the outer drum cover rotates at the same speed as the belt conveyor.

As the eddy current systems rotor spins, an electric current is induced into any conducting metals such as aluminium, copper and zinc. The induced electric current produces a magnetic field, which opposes the field created by the rotor, repelling the conducting metals over a pre-positioned splitter plate. The remaining materials fall in a normal trajectory away from the separation area, separating them from the repelled metals.

The typical material size range for this design of Metal Separation Module is between 2-40mm depending on the shape and density of the material. Bunting also supports the ReLiB project by offering researchers open access to the range of laboratory and pilot scale magnetic and electrostatic separation equipment at their Redditch testing facility.

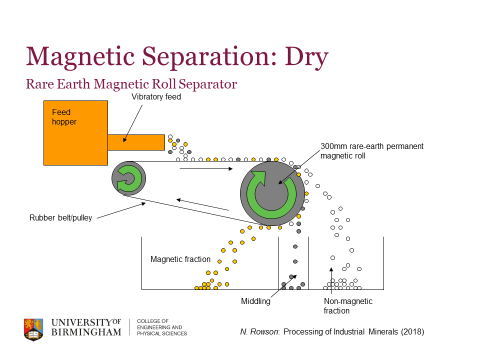

Enhanced magnetic separation of weakly magnetic components from the shredded battery is achieved using a Rare Earth Roll Separator. The Rare Earth Roll Separator uses discs of high strength Neodymium magnets sandwiched between steel poles to produce exceptionally high strength magnetic fields and gradients. The technology is used extensively in the mineral processing industry, but is increasingly used in recycling applications.

The Rare Earth Roll comprises of a magnetic head roll, non-magnetic tail pulley and a thin conveyor belt. Material is fed evenly from a vibratory feeder onto the conveyor and moved into the are of intense magnetic field. Weakly magnetic materials are attracted, with their trajectory altered. Magnetically stronger materials are deposited at the back of the back, whilst weaker magnetic particles fall directly under the head roll. Non-magnetic particles continue to flow in a normal trajectory. Carefully positioned splitters dictate the level of separation in terms of recovery and purity.

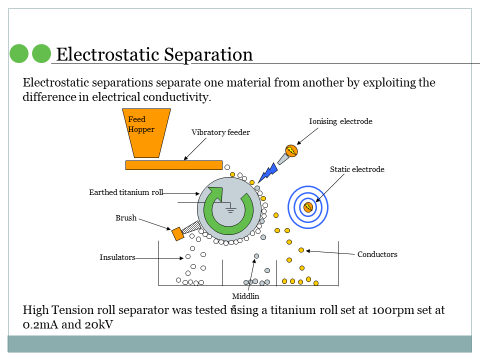

ElectroStatic Separation

The minus 2mm sized fraction is more suited to separation using an ElectroStatic Separator. The ElectroStatic Separator utilises electrostatic forces to enable a separation. In operation, materials falls onto the surface of an earthed revolving roll where they become charged by a high-tension electrode.

Conducting materials (e.g. aluminium and copper) lose their charge to the earthed roll and all in a trajectory determined by the momentum of the roll. Insulating materials generate an image charge on the roll surface and are held to the rotating roll before being discharged by the brush into a separate chute. ElectroStatic Separators are also used to separate conductor metals with different conductivity, such as copper from aluminium, with separation achieved by controlling the roll speed and splitter plate position.

Summary

There are differing opinions on the rate of growth in Electric Vehicle sales, although the decision by the UK Government to ban the sale of new petrol, diesel and hybrid cars by 2035 and measures taken by other countries will accelerate take-up. As the number of Electric Vehicles on our roads increase, so will the number reaching end-of-life. Whilst Re-Use is always the preferred option, at some point the nonviable batteries will require safe disposal and recycling. Effectively managing this ‘waste’ and recovering valuable materials is challenging. The present research being undertaken by organisations such as ReLiB and SUSMAGPRO will identify the optimum techniques to recover key materials.

This article was written by Professor Neil Rowson, Emeritus Professor in the School of Chemical Engineering at the University of Birmingham.

Additional Reference Material

- Harper G, Sommerville R, Kendrick E, Driscoll L, Slater P, Stolkin R, Walton A, Christensen P, Heidrich O, Lambert S, Abbott A, Ryder K, Gaines L & Anderson L Recycling Lithium-ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles Li-ion Car Battery Recycling. Nature journal: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1682-5

For additional information on equipment used to separate and recover metals, please contact us on:

Email: Gordon Kerr at GKerr@buntingmagnetics.com

Telephone: +44 (0) 1527 65858

Follow us on social media